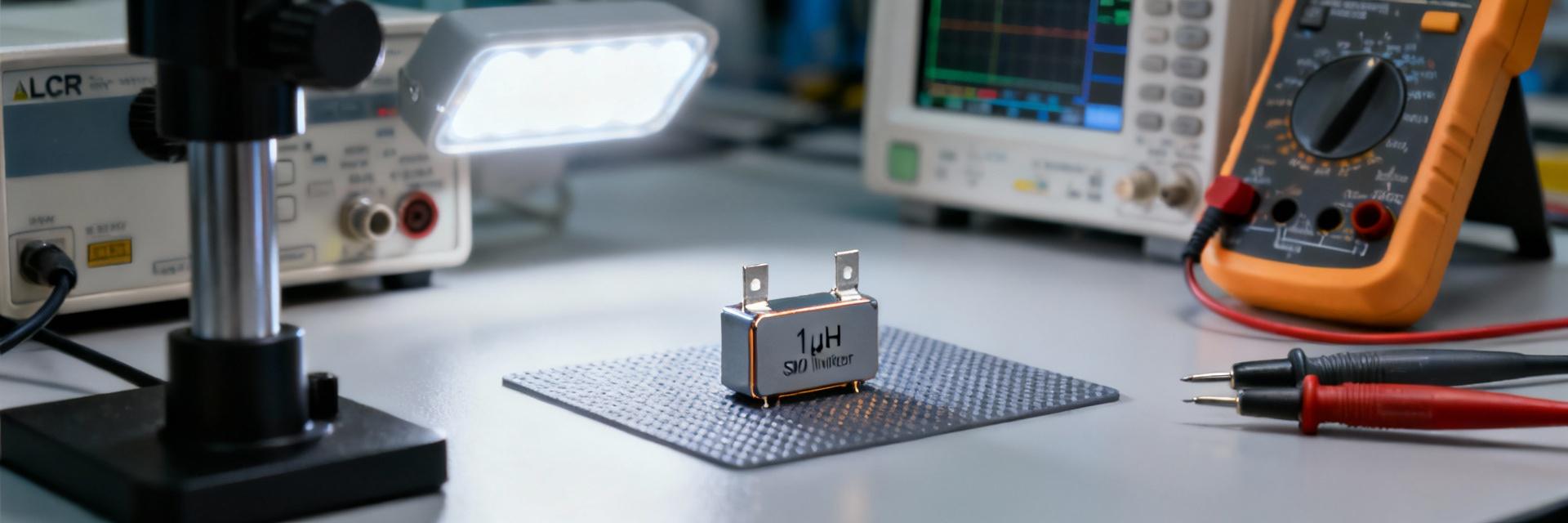

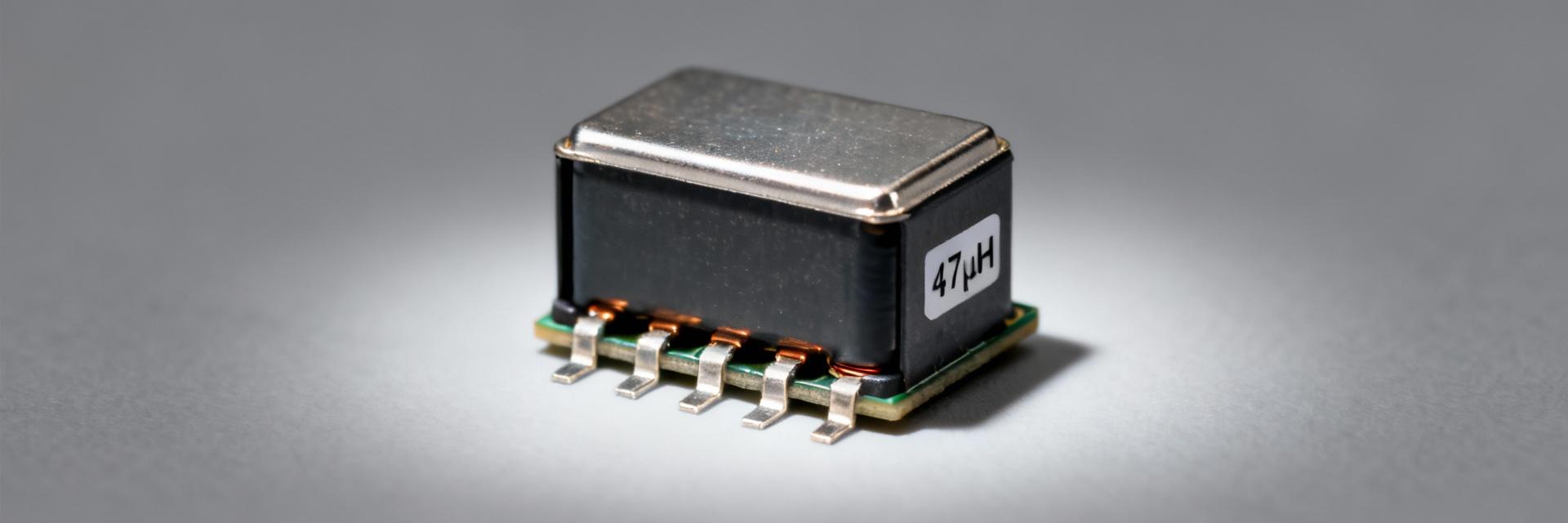

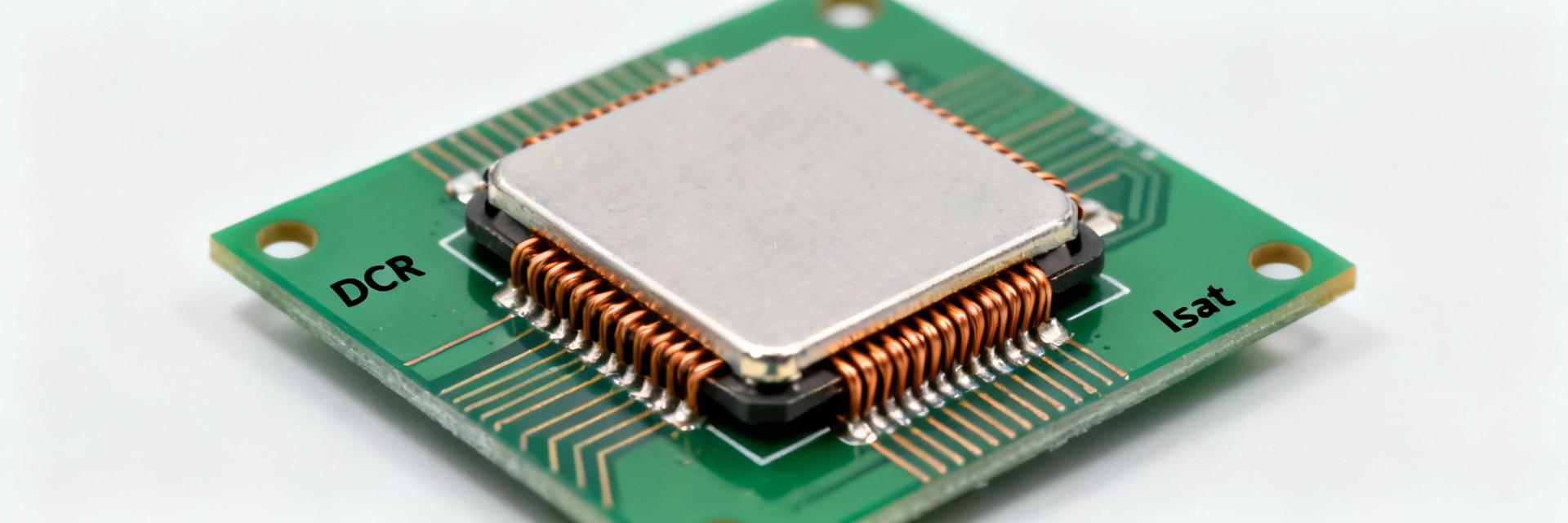

Key Insight: A 470uH SMD inductor is a compact, board‑mount passive used where substantial low‑frequency inductance is needed in a small footprint. Typical parts are wire‑wound on ferrite cores with either shielded or unshielded packages; some use molded ferrite composites for lower cost. Construction and packaging dictate DC current handling, DCR, and footprint tradeoffs important to designers.

Basic construction & common SMD packages

Construction varies from small drum‑core wire‑wound to larger molded or shielded types. Drum‑core parts commonly measure 4×3 mm to 12×12 mm footprints; shielded designs reduce EMI but increase DCR and cost. Choose wire‑wound shielded parts when current handling and EMI control matter; choose molded non‑shielded parts for minimal cost and moderate current.

Typical applications and electrical roles

Typical uses include input/output filters, low‑frequency DC‑DC energy storage, EMI chokes, and RC/LC time constant elements. In an LC output filter the inductor defines ripple current and energy storage; as an EMI choke the focus shifts to impedance at noise frequencies. Use long‑tail phrases in documentation such as "470uH SMD inductor for power filter" or "470uH SMD inductor in DC‑DC converter" to clarify intended role.

Measured Specs: How to Specify and Verify Key Parameters

Accurately specifying and verifying specs reduces field surprises. Key parameters — inductance (µH ±%), DC resistance (DCR), rated DC current & saturation current (Isat), self‑resonant frequency (SRF), Q, temperature coefficient, operating range, and dimensions — must be measured and recorded. Include suggested tolerances on the BOM and require sample verification for any parameter missing from vendor sheets.

Essential spec list & accepted tolerances

A concise checklist ensures comparability. For 470 µH parts, acceptable engineering tolerances often are:

- Inductance: ±10–20%

- DCR: Specified to ±20%

- Isat: Clear drop‑point definition

- SRF: Reported to ±10%

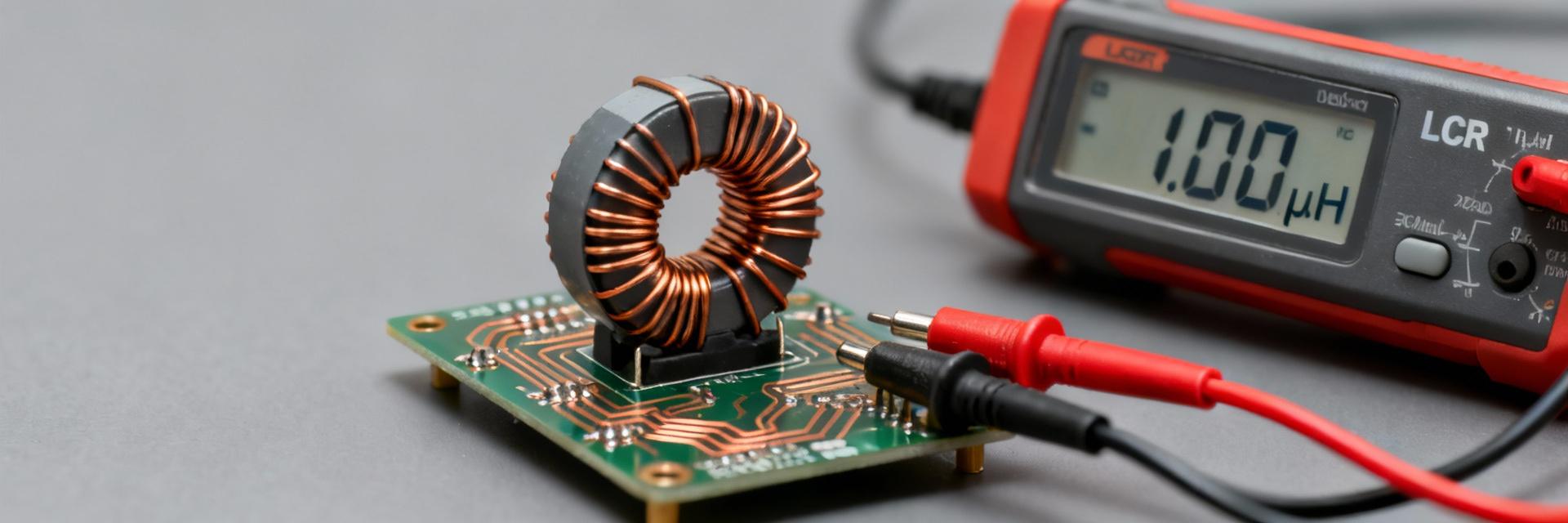

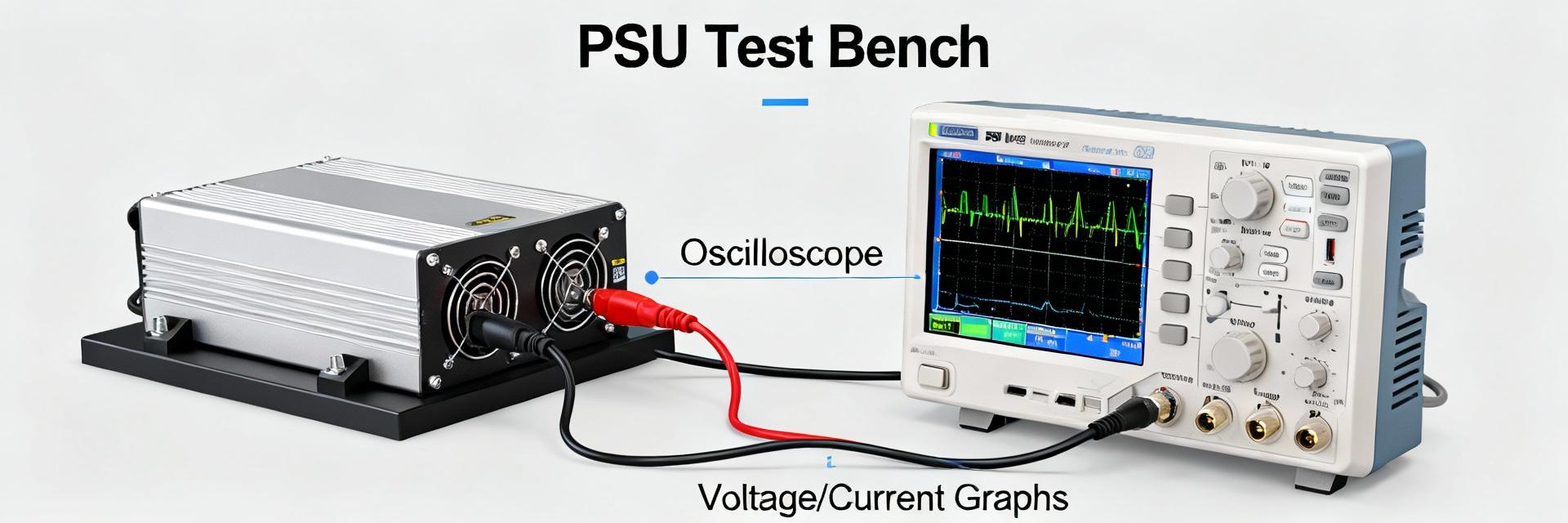

Recommended test methods

Repeatable test methods reveal real‑world behavior. Recommended procedures include:

- LCR meter measurements (100 Hz–100 kHz)

- Four‑wire DCR with a micro‑ohmmeter

- Current‑sweep saturation tests (L vs DC bias)

- Impedance vs frequency on vector analyzer

Performance Data & Analysis

A standard set of plots makes comparisons straightforward. Essential plots include L vs DC bias, impedance and phase vs frequency, Q vs frequency, DCR vs temperature, and L vs frequency to expose SRF. These curves show how inductance collapses with bias current, where loss peaks occur, and whether the SRF makes the part unsuitable above certain frequencies.

Relative Performance Benchmarks (Typical 470µH)

Typical measured curves to include

Each curve answers a specific design question. L vs DC bias quantifies ripple reduction capability; Z vs f plus phase reveals broadband impedance for EMI suppression; Q vs f indicates loss and thermal dissipation. Produce these curves for all candidate parts and compare against application requirements.

Comparative performance patterns & failure modes

Parts cluster into performance families with predictable tradeoffs. Common patterns are high‑L/low‑Isat parts for low‑frequency filters, and low‑DCR/high‑Isat parts for power storage; SRF commonly falls in the 100 kHz–few MHz band for 470 µH parts. Watch for failure signs: rapid L collapse (saturation), high temperature rise at rated current (loss), and increased DCR after thermal cycling.

Typical Use Cases & Component Selection Examples

Selection matrix: choosing a 470uH SMD inductor by application

| Application Type | Priority Parameter | Target DCR | Target Isat | SRF Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC Output Filter | Inductance Stability | > 0.2 A | > 1 MHz | |

| DC-DC Storage | Low Loss | > 0.5 A | Standard | |

| EMI Choke | Impedance Band | Moderate | N/A | Above noise band |

Example board‑level scenarios to test in prototypes

Prototype tests validate real behavior. Scenario A: LC output filter for a low‑frequency switching regulator — measure ripple, temperature rise, and efficiency impact. Scenario B: Input EMI choke for a small motor drive — measure conducted emissions and temperature. Define pass/fail thresholds (e.g., ripple within spec, temp rise

Practical Design & Testing Checklist

Pre‑production checklist (Sourcing)

- Datasheet includes L, DCR, and Isat method

- Sample testing quota for L, DCR, and thermal

- Thermal/shock/solderability qualifications

- Recommended PCB footprint verification

In‑line QA Guidance

Recommended inline tests: DCR spot checks, impedance sampling, and statistical process limits (e.g., ±3σ on DCR). Apply derating rules — e.g., limit continuous current to 70–80% of Isat at elevated temperatures.

Key Summary & Takeaways